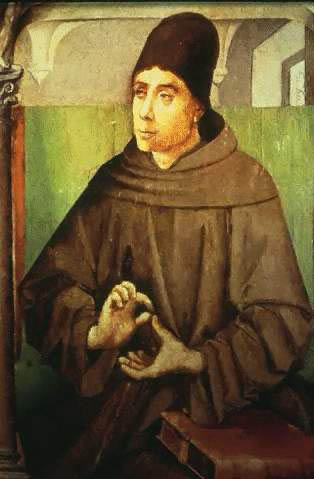

John Hare’s God’s Command, Chapter 3, “Eudaemonism,” Section 3.2.2: A Double-Source View: Scotus:

/

A contrasting view is a double-source view of motivation. Duns Scotus accepts from Anselm that there are two basic affections of the will, what Anselm calls “the affection for advantage,” and the “affection for justice.” The affection for advantage is an inclination towards our own happiness and perfection. The affection for justice is directed towards what is good in itself, regardless of its relation to us. Aristotle’s account of motivation has nothing corresponding to the affection for justice; we do everything that we do for the sake of our own happiness, even if we do not represent this to ourselves as such. Since, for Scotus, we have both affections, we face the question of how to rank them. He is not proposing that there is anything wrong with the affection for advantage. Even in heaven, we will have both affections. The affection for advantage is only wrong when it is ranked improperly. The affection for justice moderates the affection for advantage.

We can show how these can come apart counterfactually. If God were to require us, which fortunately God does not, to sacrifice even our own salvation for the sake of God’s glory, then we should be willing to do so. Hare says this thought requires a certain view about God’s election: God is not required by necessity to elect all human beings for salvation. [I’m skeptical those two concepts are connected in the way Hare pushes.]It’s a view common to Aquinas and Calvin that God not only can but does elect some for union with God (predestination), and some for separation (reprobation). [Like Hare said earlier, nearly every claim about Aquinas can be questioned.] But all that is needed for the thought experiment is that God can, not that God does. Such radical obedience repeats a pattern of thought that can be found in Moses, who says that he is willing to be blotted out of the book of life, and Paul, who says that he is willing to become a curse. Jesus too accepts separation from his Father as the price for saving his people, which was the declared motivation of both Moses and Paul. [Unclear the separation between Jesus and his Father was ontological.]

Scotus distinguishes three kinds of love we can have for God: love for God independently of any relation to us, love of union with God, and love of the satisfaction we get from that union. Lucifer started from the second of these, which is indeed something good in itself though self-indexed, and came to love it inordinately as his own advantage. We humans are now born with this wrongful ranking of the affection for advantage, and it can be reversed only by God’s assistance.

Scotus draws a connection between the two affections and freedom of the will. It is interesting Aristotle held neither a doctrine of the affection for justice in Scotus’s sense nor a doctrine of freedom of the will (though Hare admits this claim is open to doubt, as Anthony Kenny, for example, would dispute it). Scotus reports Anselm’s thought experiment of an angel who has the affection for advantage but not the affection for justice. The angel couldn’t be held accountable. It’s the affection for justice that’s needed for the liberty innate to the will.

Scotus says that neither of the affections is the rule for the other, but it’s the divine will that’s the superior rule that binds the affection for justice to moderate the affection for advantage. On the other hand, the moral goodness of the act consists mainly in its conformity with right reason, which dictates fully just how all the circumstances should be that surround the act. By “right reason” he means to include our right reason, and it is tempting to conclude from this and similar passages that Scotus is saying divine command is not necessary for the moral goodness of an act, and that therefore Scotus is not a divine command theorist at all. But remember the distinction between value and obligation. Goodness is possessed by anything that takes us to our end [notice Hare’s operative conception of goodness there; I’d put that point differently], but God has discretion over which route to this end, and so which good things to require. Only what God commands has the authority of obligation.

A second distinction is between our knowledge of moral goodness or obligation and our knowledge of what makes them good or obligatory. It’s possible that what makes something good or obligatory is some relation to God (different in the two cases), but that we can know by right reason that the thing is good or obligatory without knowing this relation. On some version of the doctrine of general revelation, God can reveal that some route to our end is required of us without our knowing that it is God who requires it.

A third distinction is between harmony or fittingness with nature and implication from nature. If God does command what fits our end, we can expect to see a harmony between this route and our end (or our nature in the sense of our end). We can expect to be able to tell a story about how, for example, we tend to flourish when we honor our parents, and refrain from murder, adultery, theft, lying, and coveting. But Scotus insists that what we see here is a harmony, or a beauty, or a fittingness, and not an implication from our nature. When we put these three distinctions together, it is plausible to say that he thinks it is God’s command that makes something morally obligatory.